"Unless they have male teachers, they would probably have zero exposure to a male doing that [reading]."

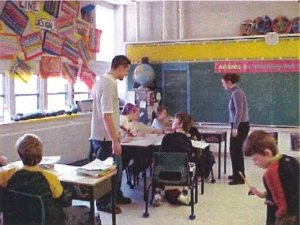

The mentors were conscious of their effect on the children. In the first year, the concerns centered on surface issues. All had been nervous about reading aloud at first, even wondering if where they sat or stood or held the book made a difference. The mentors in year one dutifully followed the mentor handbook activities that we had developed for the program. They learned their limits, remained committed to the program, and asked for help if needed. They realized the importance of building relationships with the students in an informal way, yet in an academic setting. This was not the playing field - it was the classroom and the mentors respected that difference, all the while connecting with the students. There was a refreshing honesty in the interview sessions. They often revealed that they themselves had not really liked reading or school. The growing confidence they felt in their ability to choose books and to choose response activities was evident in their final focus group meeting.

These were mainly young men who may or

may not have had much interest in books when

they were children - as reported in the

interviews. At this point in their lives, they had

been out of touch with children's reading

interests. However, in the final stages of the

project, the mentors were offering advice to the

researchers and each other and beginning to

reflect on what they had done and would do

when reading to children. They were able to

critique certain response activities that were

weak (and we agreed) and asked us to buy

books that they and the students wanted to

hear. By now, the researchers were confident

that the majority of mentors could select books

on their own for the classes with whom they

were working.