Hannon et al. (1997) propose that preschool educators change how they perceive the differences between

the way children learn, and that they recognize that parents are the experts where their child is concerned,

that parents have their own perceptions of academic literacy and of their role in their child's learning, and

that bilingual parents have different learning needs than unilingual parents. We can extend these

proposals to practitioners in family literacy programs.

Vernol-Feagans et al. (2004) maintain that the community and its professionals bear the responsibility for

understanding children who do not belong to the social mainstream and for understanding their family

cultures and their particular needs related to preparing for school. These authors are interested in the

myths that are detrimental to these children in educational settings in the community, including myths

that the parents lack motivation or skills or are dysfunctional. Practitioners must question their own

perceptions with regard to myths that give rise to a "deficiency approach" to family literacy (the idea that

the parents are lacking in ways that must be compensated for).

6.4.3 Gender-based differences

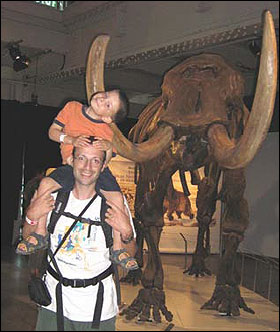

Fathers

In the For My Child reports as well as several other reports reviewed,

the observation is made that few fathers participate in family literacy

programs. It has also been noted that the majority of fathers who have

participated in the programs were enrolled in a program model

targeting parents of school-age children. This observation echoes that

of Ortiz et al. (1999), who note that a child's entry into the school

system is important to fathers.

In the For My Child reports as well as several other reports reviewed,

the observation is made that few fathers participate in family literacy

programs. It has also been noted that the majority of fathers who have

participated in the programs were enrolled in a program model

targeting parents of school-age children. This observation echoes that

of Ortiz et al. (1999), who note that a child's entry into the school

system is important to fathers.

A number of recent publications coming mainly from the United States

and the United Kingdom focus on the role of the father. In the European

project PEFaL, the suggestion has been made that in communities

where ben have greater prestige as figures of authority than women, it

is important that family literacy programs be offered mostly to women.

The research by Ortiz et al. (1999) has already been presented in chapter 4, but it is pertinent to mention it

again here. They make the following recommendations to practitioners:

- encourage fathers who already participate in programs and invite them to share their

experiences with other fathers,

- reassure fathers about the importance of their contribution to building their children's literacies, and

- help them recognize the benefits of their participation as a way of improving the emotional bond with their child.

Green (2003) has described the benefits and challenges of fathers' participation in the four-week long

American program Fathers Reading Everyday Program (FRED). In this program, the fathers read to their

child for 15 minutes a day for the first two weeks, and then 30 minutes for the last two weeks. The program

aims tal increase fathers' participation in encouraging a love of reading in their preschool and first-grade

child and in improving the quality of the father-child relationship, which in turn raises the child's potential

for academic success as well as his self-esteem. The fathers who participated in the program reported that

the program helped them read to their child every day, increased the quantity and quality of the time spent

with their child, raised their satisfaction level as a parent and improved their relationship with their child.

In the For My Child reports as well as several other reports reviewed,

the observation is made that few fathers participate in family literacy

programs. It has also been noted that the majority of fathers who have

participated in the programs were enrolled in a program model

targeting parents of school-age children. This observation echoes that

of Ortiz et al. (1999), who note that a child's entry into the school

system is important to fathers.

In the For My Child reports as well as several other reports reviewed,

the observation is made that few fathers participate in family literacy

programs. It has also been noted that the majority of fathers who have

participated in the programs were enrolled in a program model

targeting parents of school-age children. This observation echoes that

of Ortiz et al. (1999), who note that a child's entry into the school

system is important to fathers.